What do you know about worms? Or, more precisely, orange worms? Before you start thinking “Why on Earth am I reading this on a tech blog?”, let me provide you with an explanation.

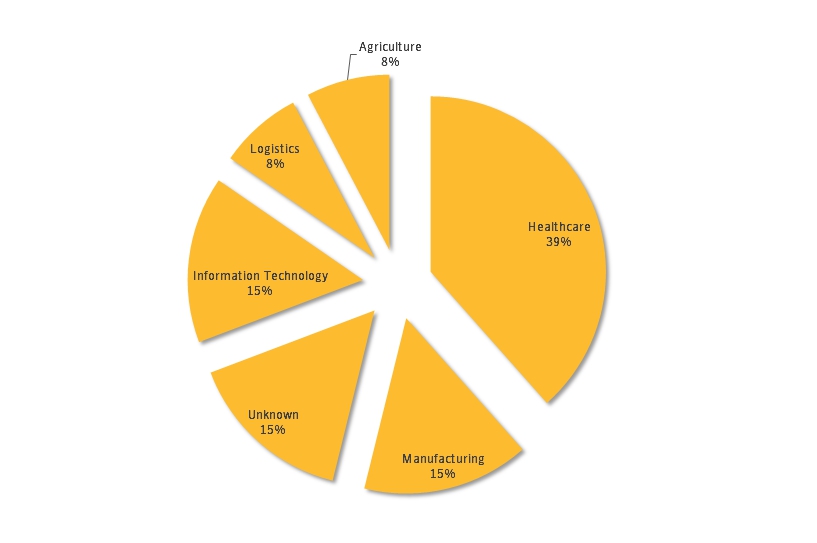

Monday, April 23rd was a really bad day for the healthcare industry as the general public around the globe has known about Orangeworm. First identified in January 2015, Orangeworm is a hacker group that conducts targeted attacks against large international corporations operating within the healthcare sector in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Despite the fact that in 2016 and 2017 the trojan impacted only a relatively small number of victims, infections were spread in multiple countries due to the nature of the business. The way they reach their goal is non-revolutionary: as part of a large supply-chain attack, cybercriminals infiltrate organizations with a custom backdoor called Trojan.Kwampirs. Let’s check the chart from Symantec, an American company providing cybersecurity software and services:

According to Symantec’s report, nearly 40% of confirmed victims represent the healthcare industry. Healthcare providers, pharmaceuticals, IT healthcare solution providers and equipment manufacturers for the healthcare industry are all included in their list of victims. The Kwampirs malware was installed on machines which had software for managing high-tech imaging devices such as X-Ray and MRI machines. Besides, hackers attacked machines which are used to assist patients in completing consent forms for required procedures.

Having penetrated into the system, Kwampirs collected basic data about the device and sent it to a remote server. Then using the backdoor on the infected machine, attackers gained access to pieces of sensitive data. If the compromised system was identified as potentially interesting, the data was stolen, as well as the process of « aggressive copying » of the malware hit any available machines and network resources. Probably, due to this aggressive and worm-like behavior, Kwampirs was found on computers that monitor the operation of X-ray machines and MRI scanners.

Based on Symantec’s investigation, the criminal group has developed a detailed plan for choosing their victims as they do not mess up with simple random hacking. On the contrary, Orangeworm selected its targets carefully and intentionally before launching an attack. The question is: what is their final goal? The specific motives of the criminal group are unknown, but most likely, they use the stolen data for corporate espionage. At the same time, Symantec analysts believe that the group hasn’t any affiliation with so-called « government hackers ». Experts suggest that the ultimate goal of the attackers could be the theft of medical organizations’ patents and their subsequent resale on the black market. Currently, there are no technical or operational indicators which may help to find out the origins of the group.

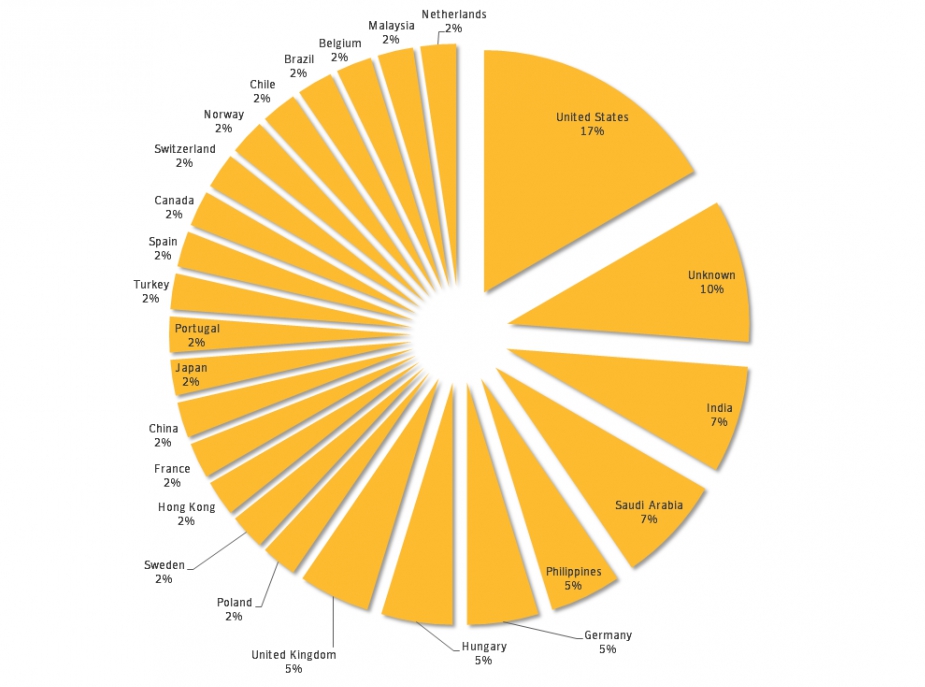

As for the victims, most of them are located in the U.S., accounting for 17% of the infection percentage by countries. India, Saudi Arabia, Germany and the UK are the next in line, with 5 to 7% respectively.

While the main “focus group” consists of healthcare organizations, their auxiliary targets come from manufacturing, information technology, agriculture, and logistics industries. Let’s hear Symantec explain these statistics: “While these industries may appear to be unrelated, we found them to have multiple links to healthcare, such as large manufacturers that produce medical imaging devices sold directly into healthcare firms, IT organizations that provide support services to medical clinics, and logistical organizations that deliver healthcare products”.

Symantec experts believe that the attacks were this successful and remained unnoticed for several years, “thanks” to the fact that there are a lot of outdated computers and software in the healthcare industry. It is not a big deal to compromise these systems as they often lack proper security solutions, so hacking couldn’t be discovered right away.

Every professional in every industry knows that security is important. Especially, in the modern era where such things are becoming a commonplace. But how to tackle the problem effectively?

Sure, the HIPAA Security Rule “requires appropriate administrative, physical and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and security of electronic protected health information,” but it doesn’t provide a step-by-step guide of any kind. What are the ways doctors can protect PHI on their medical devices? Let’s outline the most important ones.

– The identification of each and every device on the network.

Identify everything that has a network connection: tablets, mobile phones, scanners, IoT devices, desktops, and laptops, etc. If your company adheres to BYOD policy, take time to identify those users as well.

– Minimization of the PHI amount.

Simple as that: the less PHI is being stored on your device, the less likely it will be a target for hackers.

– De-identification of the information.

It’s worth to anonymize the data, especially if it’s being used for statistical or research purposes. Secondly, the de-identification notably reduces the chances of exposing PHI if a breach occurs.

– Encryption.

The data encryption is a must, no matter if it’s being transmitted to the cloud or stored on a device.

– Regular checks and updates of your Internet security tools.

- Installed and repeatedly updated security software: make sure that you have the latest tools for protecting against viruses, malware, and malicious applications.

- Protect your architecture against unauthorized connections via firewalls.

- Remote wiping and disabling: it makes sense to reduce the time the data is stored on a device. Also, it’s important to adhere to the principle of mandatory deletion of obsolete PHI and PII.

Returning to Orangeworm, there are no clues or guesses, which may reveal their identity or location. However, one way or another, the group knows what they are doing: so far, it has attacked more than 100 organizations since 2015. For what is worth these numbers mercilessly illustrate the state of IT in healthcare – how sad is that. Despite their traditional or even out-dated techniques, “it may still be viable for environments that run older operating systems such as Windows XP, » the experts from Symantec explain. Just think about it: Windows XP in 2018.

The different systems healthcare professionals are using aren’t patched on a regular basis. “Some of them are embedded systems that, due to the way the manufacturer has created them, can’t be easily patched. If the healthcare IT department were to do so, it would cause significant problems with the way the vendor can support them,” comments Perry Carpenter, chief evangelist and strategy officer at KnowBe4.

No wonder that criminals gain profits from these weaknesses and force medical institutions to pay the ransom to recover stolen data. For instance, back in 2016 Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center eventually paid 40 bitcoins, worth $17,000 this period of time, to resolve a ransomware attack. The market is active: in 2016, a database of 34,000 medical records stolen from a New York hospital was on sale for 30 bitcoins (valued at US$19,000), while another stolen database involving 690,000 medical records is selling for 643 Bitcoins (around US$411,000) – all courtesy of the dark web.

So what do you know about the orange worms? Well, now you’re informed. Forewarned is forearmed, as they say. However, it would be fair to say that improvements in healthcare cybersecurity aren’t going to happen overnight. It’s going to take time, commitment, and cooperation between organizations. The point is that even the basic practices described above can make a contribution to the better security of healthcare networks.